Robert Goutarel

Annotations by Claude de Contrecoeur

Robert Goutarel was born on March 15, 1909 at Dôle, in the Jura Department of France. He is a pharmacist, a doctor of medicine and a doctor of sciences, and was a student of professor V. Prelog, Nobel prizewinner in chemistry, at the Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich, Suisse.

Four periods in ibogaine studies are described here: the first three relate to the pharmacodynamic studies conducted in France (1864-1905; and 1940-1950) and subsequently in the United-States,essentially Ciba's work (1950-1970). The low acute and chronic toxicity of ibogaine is established (Dhahir, 1971). Ibogaine inhibits the oxidation of serotonine and catalyzes that of catecholamines by a MAO (monoamine oxidase), ceruloplasmine (Barrass and Coult, 1972). Ibogaine is a type of "hallucinogen" at high doses.

(My annotations in pink colour: This word of "hallucinogen" should cease to exist in

psychopharmacology because,first,it is a completely

prejudiced,ethnic word and,second,the "hallucinogens" do not induce

real 3 D visions but,only,very faint visual disturbances mostly

seen only in darkness. Moreover,the very word "hallucinogen" is

highly disturbing because it,magically,transforms oneirosis and imagination into

"pathology"..!

It should be emphasised,with the strongest stated

words,that enhancing the imagination in homo sapiens is something

deeply rooted in our human psyche as what,mostly,distinguishes the

species homo from other animal species is,precisely,its imagination

which gave rise to culture,religion,folklore,arts

and,finally,science.

Without Imaginationthe life of homo

sapiens would be meaningless because we,human beings,put

affective coloursall

around us,superimposed on the "real" objective

Exoreality.

All "hallucinations",weak (Imagination) or strong(

Dream) are only an expression of our internal thoughts,our

Noosphere.

They are,basically,NOT pathological otherwise the

whole Endoreality would be pathological.

The word "hallucinogen" should be replaced by the

following correct words:

1.Cogitatiogenic or Pensogenic (which increases thoughts through stimulation of the pre-frontal cortex) Reference: Psilocine.

Cogitatiogens do not stimulate consciousness radiation,like psychotropic cannabinoids.Unlike cannabinoids,cogitatiogens enhance the focussing abilities of Consciousness which can become polyfocal instead of monofocal. Thought remains in continuity.

2.Pre-Oneirogenic (which induces hypnagogic/"hypnopompic enhanced imagery,that is faint disattenuated images or sounds. For example,psilocine is both a pre-oneirogenic and a cogitatiogen while delta-9 THC is a pre-oneirogenic but not a cogitatiogen,despite the fact that,it also,stimulates thoughts!

Psychotropic cannabinoids are distinguished from cogitatiogens by the fact that they stimulate the metabolism of MHV domains,thus giving rise to a radiating form of consciousness(conscience rayonnante,en Français) and discontinuity of thought.

3.Oneirogenic (which disconnects the " I " (le Moi) from Exoreality to reconnect it within Endoreality)

References: ibogaine,salvinorin A,ketamine.

At low doses,salvinorin A is to be classified as a

pre-oneirogenic.

The Realm of the Imaginary is,basically,the hard-core of our Noosphereand,thus,should not and cannot be artificially pathologised.)

The present period began around 1960 and covers the applications of ibogaine in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis according to Naranjo (1960) and in combatting drug dependency according to Lotsof. The role of eboga in Bouiti initiation ceremonies was studied by ethnologists in Gabon. The intoxication by eboga (chewing) is slow and progressive and is characterised by four stages of oneiric manifestations. The first three stages are essentially of the Freudian type; the fourth one, called the stage of normative visions, corresponds to the collective image of the tribe, visions of the beyond and of spiritual entities, Masters of the Universe. The initiate will see the Bouiti only twice during his life, on the day of his initiation and on the day of his death, which means that the normative visions have some similarities to the near death experience (NDE). The psychotherapeutic method of Naranjo involves only the Freudian stages produced by subtoxic doses of ibogaine, while Lotsof goes beyond that stage to reach another one comparable to the normative visions or NDE, bringing about the cure of addicts(pharmacodépendants) Based on recent neuroscientific evidence concerning the mode of action of ibogaine, the US Institute on Drug Abuse

( I emphasise,here,that this word drug "abuse" is a typical ethno-word found in the anglo-saxon ethnoculture. It has no real scientific basis but,only,expresses a peculiar ethinicity.)

has added ibogaine to the list of drugs whose activity in the treatment of drug dependency is to be evaluated (after years of ignorance. This reflects the typical stupidity of "conventional" "scientists" ). Ibogaine blocks the morphine- and cocaine-induced stimulation of mesolimbic and striatal dopamine and reduces the intravenous self-administration of morphine in rats.

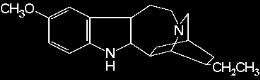

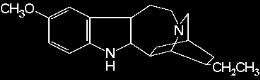

Note on the structure of ibogaine:

Chemical investigations for the purpose of establishing the structural formula of ibogaine were undertaken by two groups: a Swiss group headed by Prof. E. Schlittler (Organisch chemische Anstalt der Universität Basel), and a French-Swiss research group including Prof. V. Prelog, Nobel laureate in chemistry (Ecole Fédérale Polytechnique de Zürich, Suisse), Prof. M.M. Janot (Ecole de Pharmacie, Paris), and R. Goutarel. The discovery of ibogamine, a nonoxygenated alkaloid, the basis of the other iboga alkaloids, was published jointly by C.A. Burckhardt, R. Goutarel, M.M Janot and E. Schlittler (Helv. chim. Acta, 35, 1952, p. 642)8. Using the alkaline fusion of ibogaine, Schlittler's group isolated 1,2-dimethyl-3-ethyl-5-hydroxyindole (Schlittler, E., Burckhard, C.A., Gellert, E., Die Kalischmelze des Alkaloides Ibogain, Helv. chim. Acta, 36, 1337, 1953), while the Franco-Swiss group (Structure de l'ibogaïne, R. Goutarel, M.M. Janot, F. Mathys and V. Prelog, C.R. Acad. Sci., 237, 1953, p. 1718) characterized 3-methyl-5-ethylpyridine. The combination of these results led R. Goutarel to propose, in 1954, a formula that included all the elements of the structure of ibogaine; the definitive structure necessarily had to include a fifth ring formed by a bond between the C-17 or a carbon atom from the ethyl chain and another carbon atom of this molecule (most likely C-16).The definitive structural formula was established by W.I. Taylor (Bartlett, M. et al., 1958) in which ibogaine has an ethyl chain, following the study of the seleniated dehydrogenation products of this alkaloid. W.I. Taylor had belonged to the Franco-Swiss group before he joined Prof. Schlittler's staff at Ciba Laboratory in Summit, New Jersey, and contributed in particular to the study of cinchonamine and quinamine (R. Goutarel, M.M. Janot, V. Prelog and W.I. Taylor, Helv. chim. Acta, 33, 1950, p. 150, 164).

Clinical research, the one which is directly concerned with human illness, will be the bearer of great hopes. Philippe Lazar, Director General of INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research), Madame Figaro, No. 14110, 88 (1990) 1864-1905. The pharmacodynamic and clinical research on iboga and ibogaine may be divided into four periods. Henri Baillon, who established the genus TABERNANTHE H.Bn. at the Museum (Member of the French Academy of Sciences, Professor at the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris, Director of the Institut de Chimie des Substances Naturelles, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, 91190 Essonne, France) in 1889, and described under the name of Tabernanthe iboga H.Bn. the sample brought back from Gabon in 1864 by Dr. GRIFFON DU BELLAY, a navy surgeon, wrote:The root of this plant is the part that the Gabonese eat. They say that it is inebriating, aphrodisiac, and, with it, they claim that they feel no need for sleep. However, as early as 1885, Father Henri Neu had written in a manuscript entitled: LE GABON (Neu 1885): Most Europeans (living in Gabon) have heard about this plant, used in fetichistic ceremonies. The natives use an infusion of eboga root scrapings as a potent philter that enables one to discover hidden things and to tell the future. The one who drinks it falls into a deep sleep during which he is obsessed by uninterrupted dreams which, until the time that he awakens, he takes to be actual events...

The fact that it was recommended for physical or mental efforts by healthy individuals rapidly aroused the interest of post-war athletes (Paris-Strasbourg walking race competitors, mountain climbers, cyclists, cross-country runners, etc.).Haroun Tazieff (celebrated French geologist and volcanologist, Honorary Research Director at the CNRS) gave the following description of his experience with Lambaréné in his book, "Le gouffre de la Pierre Saint-Martin" (Arnaud publ.).

"Go ahead", said André (the expedition's doctor), "it will give you strength. And also swallow this, he added as he handed me a tablet. Do you think we should already be taking this? Shouldn't we save it until we are completely exhausted?" It was Lambaréné, a stimulant, a "doping" agent which was supposed to enable us to find the necessary strength in our exhausted bodies. "No, go ahead, what we have to do is to prevent fatigue. Later on, we'll be taking some more, regularly..." We had just swallowed our third tablet of Lambarène, and we could feel a tonic effect. I hastened, "doped up" on Lambaréné, and jumped from one boulder to the next with renewed agility... Despite the Lambaréné, I was really beginning to feel worn out and had trouble scaling the huge boulders which we immediately had to descend to start on the next one, while insidious cramps crept along the anterior portions of my thighs. I was hoping they wouldn't get worse... I took another Lambaréné. While André climbed up the ladder, I massaged my legs. Within ten minutes, everything was in order and in turn I climbed up without any difficulty... In spite of the fact that I had swallowed a Lambaréné, I really didn't feel talkative at all. Time flowed on, like a stream. One hour passed, and so did the effect of the Lambaréné...

And, on this last day, this frenzied race toward our discovery, these six hours of descent and climbing sustained by Lambaréné, this day on top of all others, it was terrible... Only the stimulant enabled us to keep going. When the effect of the last tablet had passed and I had no more, I was nothing but a pitiful package of meat miserably dangling at the end of a wire."Lambaréné disappeared from the market around 1966 and the sale of ibogaine was prohibited.

(bien sur de façon totalement arbitraire,façon n'ayant rien à faire avec la Science mais relevant de l'Inquisition et du terrorisme intellectuelle..que dire? De la Gestapo Intellectuelle) -Claude-

Since 1989, this alkaloid has been on the list of doping substances banned by the International Olympic Committee, the International Union of Cyclists and the French State Secretariat for Youth and Sports.

The study of chronic toxicity shows that when ibogaine was administered for 30 days at a dose of 10 mg/kg i.p., it caused no liver, kidney, heart or brain damage. The administration of 40 mg/kg for 12 days to 10 rats produced no pathological changes in the liver, kidneys, heart or brain. This is in contrast with the toxicity of serotonin which, at doses four times lower, causes serious damage to the kidneys: tubular dilatation and degeneration and the presence of eosinophils. Thus, ibogaine appears to be a relatively nontoxic alkaloid, particularly by oral administration, with a wide therapeutic index ranging from 10 to 50 mg as an antidepressant in humans and, as we shall see later, from 300 mg to 1 g when used for its oneiric action, the toxic doses being similar to those of aspirin and quinine. Schneider and Reinehart (1957) analyzed the cardiovascular effect of ibogaine hydrochloride in the dog and the cat and showed that at doses of 2 to 5 mg/kg, ibogaine exerts negative chronotropic and inotropic effects. The slowing of the cardiac output is responsible for the drop in blood pressure. These effects are suppressed by atropine. Gershon and Lang (1962) suggested that the changes in the electrocardiogram of the unanesthetized dog indicate that ibogaine enhances sinus arrhythmia and potentiates the vagal effects. They confirmed what had been pointed out by Raymond-Hamet: ibogaine potentiates hypertension produced by epinephrine and norepinephrine. They pointed out that the negative chronotropic activity of indole alkaloids is increased by the introduction of a methoxyl group on the indole ring. Zetler and Lessau (1972) synthesized two azepino-indoles and compared them with four indole alkaloids. These compounds have direct noncholinergic effects with negative chronotropic and inotropic actions. Neuropharmacological studies were carried out by Schneider and Sigg (1957) using isolated cat brain preparations, as well as curarized cats and dogs. The electroencephalogram shows a typical arousal syndrome when 2 to 5 mg/kg of ibogaine hydrochloride are given intravenously. They suggested that the site of action of ibogaine must be in the ascending reticular formation. Pretreatment with atropine (2 mg/kg) blocks this ibogaine-induced arousal. There is no effect on neuromuscular transmission. Numerous researchers were interested in the tremor produced by certain indole alkaloids, particularly ibogaine. This tremor is of central origin and is suppressed by atropine. In addition, Schneider explained the morphine-potentiating effect of ibogaine by its inhibiting action on cholinesterase. Finally, in 1972, in a study on the effects of some CNS-active drugs that can interact with ceruloplasmin, Barrass and Coult (1972) indicated that at a concentration equal to that of the substrate, ibogaine inhibits 50% of the oxidation of serotonin and catalyzes the oxidation of catecholamines (200%) by the copper-containing plasma globulin. They classified ibogaine among the hallucinogens and noted that LSD produces the same effects at a concentration 10 times lower. It should be noted that Naranjo (1969) explained the antifatigue and antidepressant properties of ibogaine by defining it as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI). We should add that more recently in France, Wepierre45 studied the influence of tabernanthine, an isomer of ibogaine, on the kinetic parameters of the turnover of cardiac norepinephrine in the hypoxic rat. This hypoxia can serve as a model to assess the protective action of this substance against fatigue. In addition, at Gif-sur-Yvette, in the CNRS Laboratory of Physiology of the Nervous System, Dr. Naquet demonstrated that in the cat, tabernanthine produces a calm and prolonged wakefulness, very different from the one produced by amphetamines (Da Costa, L., Sulklaper, I., Naquet, R., Rev. EEG Neurophysiol. 1980, 10, 1, 105). This wakefulness is followed by slow sleep without the anomalies that occur in REM sleep, the period of dreams (Da Costa, L. 1980).

Eboga does away with the notion of time, the present, past and future blend into one, as in the superluminous universe of Régis and Brigitte Dutheil: through the absorption of éboga, man returns to the birthplace whence he came. In order to be admitted to the Bouiti Society, the candidates must submit to a series of trials orrites of passage that begin in an enclosure strictly reserved for the initiates. Each candidate has a mother who is an old initiate; this is a man who sees to it that the initiatory ceremony is conducted properly. This ceremony consists essentially of ingesting scrapings of éboga root (Tabernanthe iboga H.Bn. var. ñoke and mbassoka). This "chewing of éboga" is supervised by the mother who constantly checks the dosage of the drug according to the physiological reactions of his candidate who must take a very large quantity of root bark and stems of T. iboga. This chewing is preceded by abstinence from sex and food the day before.

The rite is very strict and each manifestation has great symbolic value. Over a fire, the elders roast squash seeds. The sound they make as they pop symbolizes the release of the spirit -- which supposedly leaves the body through the fontanelle -- on its mystical journey. The candidate's skull is struck three times with a hammer to help free his spirit. The neophyte's tongue is pricked with a needle to give it the power to relate the visions to come. Since the chewing can last several days, the disincarnation and the reincarnation of the neophyte are reenacted before the visions appear.

The candidate is led to the river, and a miniature dugout canoe made of a leaf, bearing a lit torch of okoumé resin, is set upon the waters. This rite represents the journey of the spirit, downstream, toward the West, the setting sun, death, and symbolizes disincarnation. A stake surmounted by a diamond-shaped wooden structure is planted in midstream: it represents the female sexual organ, which the candidate must go through (in a fetal state) against the current, thus swimming upstream, from the East, the rising sun, from birth.

For the enactment of this initiatory birth, the neophyte's head is shaved and is sprinkled with a red wood (padouk), as is done with the newborn. Finally, as soon as the neophyte's psychological state after the chewing is considered satisfactory, he is led into the Temple where he is placed on the left side, symbolizing womanhood, darkness, death. He remains in the Temple, on the left side, absorbing iboga leaves until the normative perception of the visions occurs.

During the chewing, the effects of the drug begin to be manifested 20 minutes after the first absorption of éboga by violent and repeated vomiting: "The belly of the neophyte (banzié) is emptied even of its mother's milk." To go to the beyond, one has to die; the body remains on the ground with the elders, the soul departs. The physiological manifestations begin with drowsiness, followed by motor incoordination, strong agitation, tremor, crying and laughter, partial anesthesia with intermittent hypothermia and hyperthermia, panting that may go as far as choking. To assess the progress of the intoxication and to adjust the dosage, those in charge take the pulse, listen to the heartbeat, check the temperature simply by touching the body and evaluate sensibility by pricking with a needle at different times. According to the physiological state, the mothers regulate the dose of éboga up or down from time to time. The oneiric effects do not begin to be manifested until after about ten hours, during which time the aforementioned rituals take place, partly in public with dances and music. Among the Mitsogho, the subjects under the influence of éboga go through four stages to reach an image content corresponding to the required norms. The candidates are constantly questioned by the initiated elders as to the content of what they perceive. The elders are the ones who make a judgment as to the initiatory value of the vision described.

The first vision consists of hazy, incoherent, disordered images devoid of religious significance, whose authenticity is often questioned by the neophyte. The second stage is characterized by a series of apparitions of menacing looking animals that sometimes break apart and at times form together again rapidly. In the third stage, the oneiric vision clearly progresses toward the mythical stereotype. The neophyte grows more and more calm, a sign of a pleasant, peaceful vision that dispels his doubts as to the objectivity and factualness of the image perceived. The neophyte feels himself enveloped by a wind that carries him off in the twinkling of an eye, to the sound of the NGOMBI harp, to an immense village without a beginning or end.

We ought to say a word about the symbolic value of the musical bow whose melodious sounds accompany the ceremony. It represents a link between the village of the men here on earth and the village of the father in the beyond. The musical bow symbolizes the road of life and death. On the way over, voices are heard: "Who is it that you seek, stranger?" And the traveler answers: "I seek the Bouiti. The voices suddenly take on human forms that ask the question again and then respond in a chorus: "You are looking for the Bouiti. The Bouiti is us, your ancestors, we constitute the Bouiti.

The vision tends more and more to become normative. The initiates then tell the candidate: "You are on the right path, the Bouiti will soon be here. Go further on. Look, and you will find it. You must not forsake the images; take up where you left off." A voice gives the candidate his initiatory name. The neophyte is watched constantly by his mother who regulates his psychophysiological reactions to prevent him from letting terrifying phantoms interfere, for they would lead him down the wrong path, down the road of death. The fourth stage, of vision (the one that ethnologists refer to as the stage of normative visions) is the one marked by the encounter with higher spiritual entities. After a dialogue with his ancestors, the neophyte suddenly finds "his legs immobilized, before two Extraordinary Beings" who disclose that he is in the "Village des Bouiti (village of the dead). They ask him why he has come to this place. After hearing the answer of the neophyte, the "Fantastic Beings" speak again. The first one says: "My name is Nzamba-Cana, the father of humankind, the first man on earth", and the one standing to his left says: "My name is Disoumba, the mother of humankind (wife of Nzamba-Cana) and the first woman on earth." Suddenly, the "Village of the Dead" is covered with increasingly intense sparks, a "ball of light" takes shape and becomes distinct (Kombé, the sun). This ball of light questions the visitor as to the reasons for his journey. "Do you know who I am? I am the Chief of the World, I am the essential point!" This is my wife Ngondi (the moon) and these are my children (Minanga) the stars. The Bouiti is everything you have seen with your own eyes." After this dialogue, the sun and the moon change into a handsome boy and a beautiful girl.

Without any warning, the moon and the sun resume their original forms and disappear. The thunder (Ngadi) is heard and calm returns everywhere. The wind wraps around the neophyte for a second time and carries him to earth among the living. The elders greet him with pride: "He has seen the Bouiti with his own eyes", and invite him to take his place on the right side of the Temple, the side of men and of life. The candidate has become an initiate by discovering the Bouiti in another reality, that is, in the other life stemming at once from physical death and initiatory death. Through the waking dream, he catches a glimpse, in the present, past and future of his own being, of man, immutable in his spiritual essence, and living on two planes of existence. However, after the rites of passage, the new member will be isolated from the outside world for a period of one to three weeks. During this time, his meals will be prepared and served by a young woman who has recently given birth, because he is considered as a newborn. The initiate has seen, he knows, he believes, but as a Mitsogo, he will only make this journey twice: during the initiation and on the day of his death. It is out of the question for him to take éboga again under the same conditions. >From then on, the sacred plant will only be used sparingly, to "warm the heart" and to help him "in physical efforts or discussion.

We can learn several things from this study of the Mitsogo Bouiti.

First of all, there are some striking similarities between the Bouiti initiation and the freemasonery initiation rites. The end result is the same, the knowledge of the mysteries of the beyond, which the masons call the "sublime secret". Freemasonry initiation is preceded by the candidate's retreat during which he is assisted by one who has been previously initiated. The latter will convey to him, as he makes him pass through a narrow door, that the initiation is a new birth. But most astonishing, in the masonry ritual, arethe three blows on the head with a mallet, in remembrance of the assassination of Hiram, the architect of the Temple of Solomon, by three of his companions to whom he refused to reveal the "sublime secret". The only difference between the masons and the followers of the Bouiti is that the latter have the certainty of knowing this secret. The Bouiti initiation, among the Mitsogo, concerns essentially the passage from adolescence to manhood, hence the necessity of eliminating the epigenetic elements of childhood and adolescence in order to reprogram in the young man a new ego corresponding to the cultural norms of the tribe. To achieve this, the Mitsogo call on the instrumental deprivation of sleep, as the initiation lasts for days without sleep or food, as well as on pharmacological deprivation through the chewing of éboga. The result is a conscious dream without "psychotic" manifestations during which the subject remains perfectly conscious and can communicate with those around him, being at once an actor and a spectator of his visions. What is remarkable is the fact that éboga intoxication is very gradual, which makes it possible to observe several stages during these visions. Ethnologists were able to follow in the field the progression of this intoxication and to distinguish four characteristic stages during the initiation. In the first three stages, the visions correspond essentially to what the psychoanalysts call the subterranean world of Freud. The fourth stage is referred to by the ethnologists as the stage of normative visions corresponding to the collective and cultural image of the tribe (cf. Jung). While, in the Bouiti ritual, we did not fail to bring out certain similarities between the Bouitii initiation and the Freemasonry initiation, we are compelled likewise to draw analogies between certain aspects of the vision resulting from the absorption of éboga and what certain persons see at the time of clinical death. We have discussed this topic in the conclusions.

The neophyte will have to face initiatory (or real) death that will enable him to gain access to the things of the beyond. He can do so only if he has been properly prepared and, especially, if his motivation is sufficient. For various reasons - poor preparation, inadequate motivation, fear, psychosis, neurosis - certain subjects are unable to get past this critical phase. They fall prey to evil genies who veer them off onto the road of death. The elders will then decideto stop the initiation by means of an antidote whose composition is not known. We should note that the pharmacology of ibogaine has shown that atropine (an acetylcholine antagonist) suppresses all signs of ibogaine intoxication as well as ibogaine's arousal and inotropic activities.

The Omboudi (or Ombouiri, among the Fangue) is an initiatory order reserved for women who belong to the therapists among the Mitsogo and the Fangue. The women take iboga in smaller quantities than the ones taken in the Bouiti initiation. In their case, the visions do not go beyond the third (Freudian) stage during which genies, good or evil, communicate to the women that they are in possession of the causes of the affliction or illness for which they were consulted.

Along the coastal portions of Gabon, the Bouiti began to be known by the Fangue at the time that of the explorations of Savorgnan de Brazza, but according to a letter from Lucien Méyo, secretary of the Prophet Ekang Noua, "it was in 1908 that the Itsogo and Bapinzi arrived in Gabon, that is to say, in the Libreville estuary. That is where they taught the Fangue how to eat iboga by the root." Prior to that time, the Fangue used the leaves of éboga and of alan (Alchornea floribunda, an euphorbia from which Mrs. F. Khuong-Huu isolated a new alkaloid, alchorneine, but only the effects of éboga roots ultimately produce the visions of the Bouiti. The Bouiti of the Fangue, unlike that of the Mitsogo, accepts women as members, but all of them, regardless of sex, are admitted only after taking éboga. The éboga root is absorbed not only in the form of fine scrapings but also in a preparation made of cane juice or sugar, palm wine or milk. While the extraction of éboga root is reserved for the men, the "galenic preparations" are made by the women and are referred to as "express" or "automatic". Such preparations, which reduce the bitterness and partly prevent the vomiting, make it possible to achieve the phase of normative visions more rapidly. During the rites of passage, the essential features of the Mitsogo rites are preserved and the ritual language is Mitsogo. However, the "mother" is a woman, sometimes accompanied by her husband, who becomes the "father". Great importance is given to the retreat and to the confession that precede the initiation. The notion of purity is an obsession in the Fangue mentality, and the chewing is perceived as a trial that serves to expiate (by vomiting) the wrongs that have been committed. The Fangue Bouiti is actually the result of an adaptation of the original Bouiti to the traditional ancestor worship (Byérii), with the integration of Christian elements and concepts.

As a result, the Fangue Bouiti is not uniform and is structured through many branches that are independent from each other, in the midst of which "prophetic and messianic movements" flourish. According toMichel Fromaget (1986), Chairman of theDépartment de Psychologie de Libreville University from 1981 to 1983, there are two sorts of Bouiti in Gabon. The Bouiti of the Mitsogo which has been preserved in a very sober, refined form close to the original model, the initial Bouiti or Disoumba Bouiti from the name of the first woman, which has two variants: The Mitsogo Bouitii of the nganga-a-misoco, seers and divining sorcerers, eminent therapists who practice psychosomatic healing and a sort of psychoanalysis; but also: The N'déa Bouiti, a cult of sorcerers, a deviation from the Mitsogo Bouiti with human sacrifices and cannibalism, whose ultimate goal is magic, the securing of supernatural powers. The Fangue Bouiti, received mediately at a late period by the Fangues, is an astonishing syncretism with a blend of Christianity and animism. Bureau (1972) mentions 12 subdivisions in the Fangue Bouiti. Therefore, we must give up any thought of studying the Fangue Bouiti as a uniform, homogeneous entity, and it would be illusory and inaccurate to try to look for a "normative Fangue vision" comparable to the Mitsogo Bouiti. Therefore, within a community in which the initiation is to take place, everything depends on the relationships that are accepted in that community between the worship of the ancestors (represented by their skulls), the original Bouiti, and Christianity.

If we compare, in broad terms, the Fangue Bouiti and the original Bouiti we find striking similarities between the contents of the vision. Only the setting and the figures or persons represented differ. The latter are entities derived from Christianity and may appear in unlimited numbers. However, it would be a mistake to think that the Fangue Bouiti has departed completely from the original Bouiti and from the ancestral culture of the Fangues. The elements are in there, but are not very apparent. However, they can be if we know the connection between the figures that are recognized and those that are concealed behind them. A Christian religious figure may incarnate at the same time several Fangue spiritual entities, and vice versa. During the rites of passage, we find the same psychophysiological effects as the ones observed among the Mitsogo. After a long series of episodes, during his mystical ascension, the subject under the influence of éboga at its peak feels "as if transported by the wind" to the beyond before the house of Christ and of God. He is guided to that place by the ancestors, to the sound of the harp. A voice gives him his initiatory name and tells him how much money he will have to pay to be initiated. During his journey, he sees many saints, Noah, priests in their cassock. Christ, dressed in gold garments, questions the stranger as to the reason for his visit. And the neophyte answers: "I am seeking, I want to see the Lord Jesus Christ". "I am the one you seek", Christ replies. From one neophyte to the next, the content of the narratives describe encounters with Christ in some other setting. The subject first goes through "purgatory, where men suffer", then on to heaven with its seven planes where angels glide. At the highest plane, the traveler sees a man bearing a cross, and further on the beard of God the Father. In other visions, the Virgin Mary, Adam, and Lucifer appear. The dialogue is practically identical in each vision with the dialogue reported among the Mitsogo.

In this syncretism, Nyingon (the female principle or the first woman, called Disoumba among the Mitsogo) is assimilated both to Eve and to the Virgin Mary. As for Nzamé, the male principle, the first man, or Nzamba-Cana among the Mitsogo, he is represented by Jesus Christ. To certain prophets, Adam and Christ personnify Ngoroyo-Ama, that is to say, the "Supreme Being", who is never perceived in the Mitsogo vision. Lucifer, the rainbow-serpent, is present in the Fangue vision. He represents evil, that is, Evus, a well-known notion among the Fangues. In their lifetime, the Fangue can make several journeys under the ritual conditions of the Bouiti, enabling them to confirm the reality of their visions. The initiates may also belong to the Ombouiri possession society (reserved for women and called omboudi among the Mitsogo). This society, which plays a great role in medical diagnosis, is characterized by the vision, under the influence of éboga, of genies who during the course of public divinatory sessions will reveal the nature of the affliction suffered by the patient who has come for consultation. Inthe Ombouiri, we can note some similarity with Voudou in the Caribbean and South America. Among the Mitsogo, the normative vision is that of the whole tribe and corresponds in the initiate to the knowledge recorded orally since in his childhood within the tribe. With the Fangue, we observe many differences because of the changes and turnovers that may have taken place in the initiatory experience, the influence of Christianity and the competition among various more or less orthodox messianic and prophetic movements, and the loss of the tribal notion. Some whites, most of them French, have voluntarily gone through the trial of chewing of éboga. A few of them were able to be interviewed. A study of the the interpretation of these interviews is in progress at this time (O. Gollnhofer and R. Sillans).

"the points of greatest interest insofar as psychological exploration and psychotherapy are concerned."Harmaline was isolated in 1841 by Goebel from the seeds of a plant of the family Malpighiaceae, Peganum harmala. It has also been extracted from another South American Malpighia, Banisteriopsis caapi or yagé. Yagé bark is the principal ingredient of the beverage used by the Indians of the region of the headwaters of the Amazon in connection with certain divination rites and practices and it is known, according to research done at the University of Chile, that this drug was central to the culture of different Indian tribes as far back as the paleolithic period. The effects of harmaline and of ibogaine are practically unique among the psychoactive drugs. The best term to describe these effects is the one used by William Turner, a yagé specialist, oneirophrenia, to refer to the states induced by drugs that differ from psychotomimetic states by the absence of any psychotic symptom while sharing with the psychotic or psychotomimetic experience the preeminence of a primary thought process (inappropriate term - Claude). Harmaline and ibogaine are characterized in their psychological effects by a state such that it involves a dream phenomenon (not correct - Claude) without loss of consciousness or change in the perception of the environment or any illusions or formal deterioration of thought (dream is characterised by thought disturbances- Claude) and without depersonalisation. In a word, we can say that there is an enhancement of imagination which is remarkable in that it does not interfere with the ego.

Such imaginations are more like actual visions than common everyday dreams. In a study on the psychological effects ofharmaline performed in Chile in 1963-64 together with other Chilean physicians and with Indian traditional therapists, Naranjo pointed out that one of the most remarkable aspects of these imaginary images is its great consistency. The themes or images that are evoked are mostly archetypes, according to Jung's definition of the term, namely ancient memories, generally common to all humans, buried in their collective unconscious.

(The "collective unconscious" seems mostly related to the structure of Memory in fractal-like MHV domains...and has nothing to do with ancient "memories".)

To cite Voltaire: "The world, according to Plato, was composed of archetypal ideas that always remained deep in the brain."

(They are directly born within the MHV structure of Memory interacting with Exoreality)

Naranjo distinguishes between two sorts of archetypes: The mythical style similar to the dream of a lost treasure, a kind old man, an ideal woman, a saint, an ideal community and various so-called noble thoughts, and so on. The instinctive style such as it may be expressed in a fantasy with aggression, sex, bloody scenes of all sorts, incest or other practices. By their spontaneity, these waking dream sequences are more extreme than any other reported by patients from their usual dreams and do not resemble the visions on mescaline or LSD. In fact, the effects of the two types of drugs seem to be poles part, those of the common hallucinogens being a high and angelic domain of esthetic sensations, of a lack of union with anything else, while the domain of the oneirophrenics is that of Freud's subterranean world of animal impulse and regression.

(See:From Dream to Consciousness)

Naranjo gives some examples of subjects treated successfully with harmaline at doses of 4-5 mg/kg orally (about 300 mg). Concerning ibogaine, Naranjo says that he knows less than about harmaline as regards the use of éboga by the Gabonese and Congolese. He is unacquainted with the Bouiti and apparently does not know the structure of ibogaine. He knows that the drug has been used in the European pharmacopeia for its antifatigue properties at a low dose, which, according to him, is due to the fact that it is a MAOI.

As with harmaline, Naranjo uses ibogaine at doses of 4-5 mg/kg orally and one-quarter of it intravenously, and describes subjective reactions lasting about 6 hours.

Compared with the effects of harmaline, those of ibogaine appear less exotic. Even though the archetypal contents are common to both (visions of animals being frequent), the quality of the fantasy is generally more personal and concerns the subject himself, his parents and significant others. At the same time, the fantasy evoked by ibogaine is easier for the subjects to manipulate, either on their own initiative or through the psychotherapist, so that, more often than with other drugs, they can stop to contemplate a scene, go back, explore an alternative in a given sequence, bring a previous scene back to life, etc.

This ease with which the events in a treatment with ibogaine can be manipulated and the fact that the experience can be directed to the desired area is probably one of the reasons for the success observed by many psychotherapists who have used this drug. Naranjo was much more impressed by the effects obtained in an ibogaine session than with those observed with any other drug. An example really shows the ease with which the psychotherapist is able to direct his analysis: This is a young patient who, when treated with ibogaine, decides to lie down and close his eyes shortly after feeling the effects of the drug: "First, he sees the face of his father, facing him as though they were playing a game, with a restrained smile. His comment at this point is that his father looks like a little boy to him. It was like someone unfamiliar and yet familiar, like something the patient had forgotten for many years. Suddenly his father's features change, distorted by rage. The scene changes and the patient sees a naked woman hiding her face with her arm, afraid. Close by, he sees his father, also naked, throwing himself on the woman in a sexual attack. He feels a controlled rage in the woman whom he now identifies as his mother." At that moment, Naranjo asks the subject to have his father and mother engage in conversation, intending in this way to distance the latent content of these images. "What is she saying?" "Go away"; "what does he feel?" He cannot imagine. "I am perplexed", he suggests. Naranjo then chooses another tack to make the subject's feelings more conscious and explicit. "Now, you be your father. Become your father, to the best of your dramatic abilities, and listen to what he is telling you." Then, personifying his father, the patient falls, not into perplexity, but into a great sadness, suffering and rejecting his anguish.

Shortly after this episode, a drastic change occurred in the way the subject viewed his parents and, consequently, in his feelings toward them. The next day, he commented that only now did he know how much he identified with his mother, looking at things through her eyes, blaming his father, and more than that, a man, which had interfered with his own masculine aspirations. In contrast to his usual idealisation of his mother in a total love and his perception of his father as a selfish brute, he then had the feeling of knowing them as they are. He wrote: "I have seen my mother as a hard person, without affection or fear, and I no longer look upon my father as an insensitive being who had hurt her in his love affairs, but as someone who wishes to open the door of his love, without succeeding. Now, I am full of compassion for my mother." Compared to the dramatic quality of psychedelic experiences, this episode may appear insignificant or trivial, and yet it was the key to a radical change in the attitudes of the young patient. That might be said of the experiences with ibogaine in general, when we compare its effects with those of LSD. Here, the type of contact concerned by the unconscious material is symbolic (rather than assuming the form of a free-floating emotion, as with LSD), and may henceforth be assimilated in the form of lasting signs. Such signs generally occur when a fantasy or a hypothesis that had been unconscious becomes conscious with such clarity that the ego of a mature person is compelled to become aware of his or her deep-rooted former error. Naranjo concludes as follows: "I do not want to give the impression that I regard ibogaine as a psychiatric panacea that will bring changes by itself. I believe that many drugs may be used for psychological exploration, but that these drugs can only be an instrument.

I doubt that there is anything that can be achieved with a drug that cannot be done without it. However, drugs can be psychological catalysts that make it possible to compress a very lengthy psychotherapeutic process into a shorter time and change its prognosis. Although ibogaine cannot open a door by itself, it can be considered as the oil for its hinges".

At the time of the publication of his report on drugs that enhance fantasies, in June 1969, C. Naranjo, together with a French, D.P.M. Bocher, obtained a special drug patent in France pursuant to an application submitted on January 31, 1968 and issued on July 31, 1969, for:

"A new medication acting on the central nervous system that can be used in psychotherapeutic treatments and as an antidrug preparation". (Bocher, D.P. & Naranjo, C. 1969).The drug was composed of total alkaloids of Tabernanthe iboga roots combined with an amphetamine in a proportion varying according to the behavior of the patient. Among the 50 cases studied in psychiatry, Naranjo described four in support of his application for a "nontoxic drug that clarifies thoughts and permits a very thorough introspection while preserving the patient's emotional character which is indispensable for the stimulation of thought and imagination." However, in this same period, following the resolutions of the World Health Assembly of May 1967 and May 1968, the US federal government classified ibogaine, through the F.D.A.(as usual the usual middle-age Inquisition comes frrom the US Intellectual Gestapo: the FDA... -Claude-), among the substances analogous to lysergides and to certain CNS stimulants. "Whereas, in the interest of public health(grotesque!), certain regulatory provisions should be applied relating to the manufacture, transportation, possession, sale and distribution, delivery and acquisition for valuable consideration or free of charge of soporific and narcotic substances, and of certain substances likely to produce drug dependency or endanger human health". These regulations are applicable to the following substances, to their isomers, unless expressly exempted, to their salts, ethers and esters, as well as to the salts of said ethers and esters in all cases where such salts may exist. The list of these substances includes: amphetamines, ibogaine, compounds and derivatives of lysergic acid, amides of lysergic acids and other derivatives, peyotl and mescaline [harmaline is not mentioned], hallucinogenic mushrooms, psilocybine and derivatives of dimethyltryptamine, psilocine and 5-OH-DMT.We shall return later to this decree which was applicable beginning in 1970 in several European countries, France and Belgium in particular (following US Intellectual Gestapo - Claude) The fact is that in France and in Belgium, nothing more was heard about ibogaine and the sale of Lambaréné was prohibited (a good example of the effects of the puritan United States worldwide inquisition! Claude).

Lotsof describes the effects of the oral administration of ibogaine and divides these effects into three stages, comparable to the four stages of the Bouiti of the Mitsogo. These three stages are described perfectly in the interview by the journalist Max Cantor with a 44-year-old subject who had been a cocaine addict for more than eight years and was treated by the Lotsof procedure.

(This is frequently observed at the onset of penetrating into a Conscious Dream...)

and an oscillating sound. Objects appear to vibrate intensely. The first visions appear after an hour. Suddenly, on the walls, there appears ascreen

(This is just like in the beginning of a Conscious Dream,after the buzzing sound.)

on which the subject views pictures that may be archetypes, more or less deformed animals, an abyss lit up by lightning, etc., or more personal episodes related either to childhood or to more recent events. The subject may question the persons he sees, identify with one of them, be at the same time a spectator and an actor. He views a film of his subconscious and his repressed memories. He looks within himself.

5 to 10 hours later, the visions cease and cutaneous sensitivity begins to return. This stage is marked by an unusually high energy that lasts 5 to 8 hours, during which the subject see flashes of light around him. Then comes what the subject calls the question-and-answer period. He analyses the visions that he remembers, seeks an interpretation and may communicate with the people around him. Ibogaine shows him where his problem is. He has the impression that a reset button has been actuated.

(Interesting as Gamma-OH gives,also,a feeling of "general reset")

Everything is erased, everything becomes sharp and clear. He knows where his life took the wrong turn and what he must do to get back on the right path. This question-and-answer period may last 20 hours, during which the subject remains under medical supervision.

the subject remains awake from a residual stimulation for up to 20 hours and then goes to sleep for as short a period as two hours and will wake up in top form, provided he is young and his general health had been good previously, with a new self-confidence, feeling no more need to take drugs.

(Note: Siamese have used mitragyna speciosa leaves in opiate addiction. Mitragyna leaves induce a strong sense of laziness at small doses!)

A spectacular sequence presented to Madame Barzach and shown on television on the program 7/7 hosted by Madame Sinclair was the vomiting of the patients who, according to the commentator, had to get rid of the poisons in their system. Unfortunately, the drug was being kept secret, and it was said that Minister Chalandon had sent an observer over there to learn the secret (Mitragynine?). That secret seems obvious to us (Not to me as there is no report of use of such apocynaceae in Siam... - Claude), and we know Apocynaceous plants from Asia containing ibogaine derivatives which, in all likelihood, have the same oneirophrenic properties as the latter.

At this time, Mr. Lotsof, who went to Gabon to collect a certain quantity of éboga, is having experiments pursued in several countries. Excellent results are being reported in the European and North American press. There have been several interviews with subjects successfully treated by the Lotsof procedure. Thanks to him, basic research is being conducted at Erasmus University of Rotterdam, at the Addiction Research Foundation in Toronto, at Albany Medical College, N.Y., and through the Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence of the N.I.H., Bethesda, Maryland, for the purpose of investigating the different body systems, the CNS in particular, in which ibogaine is involved. Blockade of morphine-induced stimulation of mesolimbic and striatal dopamine by ibogaine has recently been demonstrated by the Albany Medical College researchers.

The 1967-68 resolutions of the World Health Assembly

(Based on what researches?)

classified ibogaine among the drugs capable of producing dependency or impairing human health. When all is said and done, this alkaloid had been found guilty (that is the correct term: found guilty by the US puritanical Inquisition - Claude) of the charge of being a hallucinogen (according to this Inquisition hallucinogen = Devil - Claude) similar to LSD, whose hazards for those who use it had recently come to light. The fact is, however, that even though ibogaine is considered as a hallucinogen, it produces no drug dependency and it has proved to suppress dependency to opiates, amphetamines, cocaine, LSD and even alcohol and tobacco. As for "impairing human health", the Gabonese experience showsthat this is simply not true, quite the contrary.

The 1967-68 decree never did put an end to the illegal trade in amphetamines nor to the trade in LSD. However, on that market, one never finds éboga or ibogaine. According to Dhahir (1971), the appearance of ibogaine on the illegal drug market was reported in 1967 by the police of Suffolk County, N.Y., on a single occasion, when it was used to dilute heroin, and after Haight Ashbury it was reportedly used by young addicts in San Francisco as a substitute for LSD. Ibogaine suddenly disappeared from the market and it seems that the drug dealers rapidly became aware of the fact that its use would deprive them of part of their clientele.

Women can be initiated in the Fangue Bouiti and many differences are observed due to the changes in the initiatory experience that may have occurred under the influence of Christianity and the competition among the various more or less orthodox messianic and prophetic movements and the loss of the tribal notion. Therefore, it is out of the question to speak of normative visions in the Fangue Bouiti, which is a real syncretism between ancestor worship and Christianity. When all is said and done, the visions correspond to the culture of the future initiate: Christian and Western culture for whites who are initiated into the Fangue Bouiti.

The doses of ibogaine used in psychotherapy according to Naranjo are relatively low, and the session does not last more than 6 hours. The dose of 300mg orally appears to be the minimum required for triggering the visions analyzed by the psychotherapist who constantly guides the patients as he searches for the deep-seated causes of the neurosis for which the patient has consulted him. It appears that the sessions have to be repeated. Naranjo's conclusion is that ibogaine cannot produce the changes just by itself, hence the need for a psychotherapist.

In the treatment of drug addicts, H. Lotsof gives a single dose of about 1g of ibogaine hydrochloride orally. The session is quite long, about 36 hours, which is comparable to what is observed during the initiation into the Bouiti, given that the slow chewing of éboga and the accompanying rites are dispensed with. We might note that in the Fangue Bouiti, the session also lasts approximately 36 hours when the so-called "express" or "automatic" galenic preparation is substituted for the iboga scrapings. Thus, the first visions appear 2 hours after the ingestion of ibogaine hydrochloride. The three phases described by Lotsof are comparable to the four phases of the Mitsogo Bouiti, the first phase being that of Freudian type visions, and the second phase ("questions and answers") being comparable to the phase of normative visions. Lotsof describes a third phase, which is one of restorative sleep of short duration. We should point out that in all likelihood, the success of the Lotsof method also depends on a deep motivation of the subject who is treated, which is the will to eliminate all drug dependency.

However, new techniques developed by researchers in the neurosciences have recently provided some definite information as to the mechanism of action of ibogaine in the treatment of addicts (morphine and cocaine). Using microdialysis, Di Chiara and Imperato (1988) reported that acute administration of amphetamine, cocaine, morphine, nicotine and ethanol, all known to be addictive drugs, increases the extracellular dopamine (DA) levels in the nucleus accumbens and to a lesser extent in the striatum. I.M. Maisonneuve (1991) showed that ibogaine blocks the morphine-induced stimulation of mesolimbic and striatal dopamine. Curiously, it appears that ibogaine affects brain DA systems for a period of time that exceeds its elimination from the body and during this time alters the responses of these systems to morphine. Furthermore, ibogaine alters cocaine-induced accumbens dopamine neurotransmission (Broderick, P.A., 1991). Ibogaine reduced the cocaine-induced locomotor stimulation when given two hours before an acute injection of cocaine to mice. This stimulation is also reduced when a second injection of cocaine is given 24 hours later (H. Sershen, 1992). Finally, S.D. Glick (1991) demonstrated that ibogaine reduces the intravenous self-administration of morphine in rats, not only in the hour after ibogaine treatment (acute effect) but also one day or more later (after-effect). Since ibogaine is eliminated rapidly14, the persistence of this after-effect suggests the formation of a metabolite of ibogaine with a long half-life. Barrass, B.C. and Coult (1972) had shown that ibogaine inhibits the oxidation of serotonin by a monoamine oxidase (MAO), ceruloplasmin, and catalyzes the oxidation of catecholamines by the same substrate. Indeed, ibogaine is a potent serotoninergic that has ability to reduce the level of cerebral catecholamines. This decrease in the level of catecholamines,dopamine in particular, explains the results described recently on the blockade of the stimulation of mesolimbic and striatal dopamine induced by morphine or cocaine. We should point out that ibogaine is not specific to morphine and cocaine but is active in the presence of all addictive drugs, which justifies the patent applications that followed the initial patent of H.S. Lotsof. The decrease in the level of catecholamines and the joint increase in the cerebral serotonin level result in asuppression of REM sleep and the appearance of the hallucinatory phenomenon (C. Debru, 1990). LSD, like ibogaine, is a potent serotoninergic that inhibits the oxidation of serotonin and catalyzes the oxidation of catecholamines by MAO.

However, there is an enormous difference between these two alkaloids: LSD is active at doses of less than a milligram. Its activity is difficult to control and the hallucinatory phenomena produced belong to a high and angelic domain of esthetic sensations, whereas ibogaine is hallucinogenic only at doses in excess of 100mg, and the domain of this oneirophrenic substance is that of the subterranean world of Freud, of animal impulse and of regression. The toxicity of ibogaine is very low, lower than that of aspirin, which makes this alkaloid easy to use. The initiated masters in the Bouiti have an antidote that enables them to interrupt at any time the course of the visions if, for any reason, the absorption of iboga were to be actually life-threatening for the neophyte. Let us note that serotonine is the neurotransmitter of the cerebral parasympathetic system, catecholamines being neurotransmitters in the cerebral orthosympathetic system, and that the negative chronotropic and inotropic effects as well as the arousal-producing action of ibogaine are nullified by atropine, an acetylcholine antagonist, acetylcholine being the neurotransmitter of the autonomic nervous system. The long waking dream period that follows the absorption of iboga or ibogaine at a subtoxic dose (or oneirophrenic dose according to Naranjo) appears to be responsible for a temporary destructuring of the ego, followed by its restructuring. According to the Mitsogo, the initiate will see the Bouiti only twice in his life: on the day of his initiation and on the day of his death. This means that the visions at the approach of death, what are called near death experiences (NDE), are the same as those termed normative visions. We know that at the time of dying,some individuals see their whole life pass before them. In those who are "rescued from death", a spectacular transformation is observed. They no longer fear death, they feel stronger, more optimistic, calmer, and contemplate their life more positively.

(Same with Gamma-OH and Psilocine,at least in my case!)

Two Americans, the psychiatrist Raymond Moody39 and the cardiologist Michael B. Sabom49 have been particularly interested in theoneiric manifestations of NDE. After a statistical study of 150 people "rescued from death", M.B. Sabom established a chart of these manifestations.

Most of these manifestations are to be found in the Bouiti. Starting at the 3rd stage, a peaceful and agreeable vision, disembodiment; the neophyte feels himself wrapped up by a wind that carries him off to an unknown village without beginning or end; a vision of two extraordinary Beings, Nzamba-Cana, the first man and Disommba, the first woman on earth. The village is covered by sparks, then a brilliant ball of light appears, the sun, and the moon and the stars. The sun is transformed into a handsome youth, the Master of the World, and the moon into a beautiful woman, his wife, the mother of his children, the stars. The wind carries the initiate back to earth where he is reborn and is greeted with joy and pride by the elders. In the Fangue Bouiti, where we have a syncretism between the religion of the ancestors and Christianity, it is difficult, because of many divergent forms, to describe a coherent whole corresponding to the normative visions of the Mitsogos.

This is the question-and-answer period described by one of the subjects treated according to H.S. Lotsof. What is important is thatthis luminous phase of questions and answers is followed by a restorative sleep from which the subject awakens in great form and with a new self-confidence. Lotsof notes that the first three stages together last 24 to 48 hours or longer, followed by only 3 to 4 hours of sleep. This reduced need for sleep may continue for 1 to 4 months. The persistence of this long-term effect is consistent with the hypothesis (I.M. Maisonneuve, 1991; S.D. Glick, 1991) of a metabolite of ibogaine with a long half-life. Some subjects treated according to Lotsof retain for a fairly long time the impression of being under the influence of ibogaine. A young Dutch woman wrote: "I lost a great deal of interest in drugs in general, because the effect of ibogaine goes far beyond their effect, though not necessarily in a pleasant way", and "Up until four months after the treatment, I kept experiencing colors and light very intensely." The conclusion of the report that was written recently by this 25-year-old woman six months after a treatment with ibogaine shows that this alkaloid produced a real change in what she calls her "addictive ego", and also shows the necessity of having a strong motivation. "Ibogaine was a mental process for me, a form of spiritual purification and a truth serum in which I had to experience its results through time. It's only now, after six months, that I can say I am not addicted anymore. It takes time to admit that there is no way back. Ibogaine is not a solution in itself, although it takes away withdrawal completely. Ibogaine helps you to realize that all knowledge is available to cure yourself through will power. It's up to you if you are ready to give up your addictive ego."

The recent decision of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to add ibogaine to the list of drugs whose activity in the treatment of drug dependency is to be evaluated should prompt the competent authorities in European countries to engage rapidly along the same lines. This applies to France in particular, where research on iboga and its alkaloids began at the end of the 19th century and has continued well beyond the second half of the 20th century. If we consider all the pharmacodynamic and therapeutic investigations conducted on iboga and ibogaine, we may conclude that this alkaloid, unjustly condemned as a hallucinogen(quel primitivisme), is a key that opens the door of the fascinating realm of today's neurosciences, and we should like to see the creation of a multidisciplinary organization including ethnologists, medical doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists, chemists, pharmacists and pharmacologists, and even technical writers, so that we can get a definite opinion on the psychotherapeutic properties of iboga and ibogaine, whose use must now take place under the norms of pharmaceutical development and medical ethical review.

Barras, B.C. and Coult, D.B. 1972. Effects of some centrally-acting drugs on caeruloplasmin. Progress in Brain Res. 36, 97-104 (1972).

Bartlett, M.; Dickel, D.F.; Taylor, W.I. 1958. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. Vol. 80:126.

Binet, J.; Gollnhofer, O.; Sillans, R. 1972. Cahiers d'Études africaines vol. 46(Xii/195):253.

Bocher, D.P. and Naranjo, C. 1969. Nouveau médicament agissant au niveau du SNC, anti-drogue (A New CNS-active Medication for Use Against Drugs). Bulletin Officiel de la Propriété Industrielle, No. 35, September 1, 1969 (Special Drug Patent P.V. No. 138.081, No. 7131M, Int. Class. A 61k).

Broderick, P.A. and Phelan, T.T. 1991 (January 15). The African alkaloid ibogaine alters cocaine-induced accumbens dopamine neurotransmission: in vivo voltametric studies on the conscious brain. CPDD Abstract form.

Bureau, R., La religion de l'éboga. Essai sur le Bouiti fangue (The Religion of Eboga. Essay on the Fangue Bouiti. Thesis, Paris V, 317 pp., 1972.

Burckhardt, C.A., Goutarel, R., Janot, M.M., and Schlittler, E., 1952. Helv. chim. Acta 35, 642.

Closmenil, A. de. 1905.De l'iboga et de l'ibogaïne (Iboga and Ibogaine). Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine, Paris.

Crick, F. 1979. Réflexions sur le cerveau (Reflections on the Brain). Pour la science Vol. 25(Nov.):168.

Dacosta, L.; Sulklaper, I; Naquet, R. 1980. Rev. E.E.G. Neurophysiol. Vol. 10(1):105.

Debru, C., 1990. Neurophysiologie du rêve (The Neurophysiology of Dreams), Paris, Hermann, Edition des Sciences et des Arts.

Delourme-Houdé, J. 1944. Contribution à l'étude de l'iboga (Contribution to the study of iboga). Thesis for Doctor's Degree (Pharmacy), Paris University; Ann. Pharm. Fr. Vol. 430, 1946.

Dhahir, H.I. 1971. A comparative study on the toxicity of ibogaine and serotonin. Thesis, Ph.D. In Toxicology, Indiana University.

Di Chiara, G. and Imperato, A. 1988. Drugs "abused" by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. Vol. 85:5274.

Dutheil, R. and Dutheil, B., L'Homme superlumineux (The Superluminous Man), Sand Publ., 1990.

Dybowski, J. and Landrin, E. 1901. C.R. Acad. Sci. Vol. 133:748.

Fromaget, M., 1986. Contribution of the Mitsogo Bouiti to the Anthropology of the Imaginary: A Case of Divinatory Diagnosis in Gabon, Anthropos 81, 87-107.

Gaignault, J.C. & Delourme-Houdé, J. 1977. Les alcaloïdes de l'iboga (Iboga alkaloids). Fitoterapia Vol. 48(6):243.

Gershon, S. and Lang, W.J. 1962. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Vol. 135:31.

Glick, S.D.; Rossman, K.; Steindorf, S.; Maisonneuve, I.M.; Carlson, J.M. 1991. Effects and after-effects of ibogaine on morphine self-administration in rats. European J. Pharmacol. 195(1991):341-345.

Goebel, F. 1841. Ann. Vol. 38:363.

Gollnhofer, O. & Sillans, R. 1985. Usages rituels de l'iboga au Gabon (Ritual Uses of Iboga in Gabon). Psychotropes Vol. 2(3):95-108.

Gollnhofer, O. & Sillans, R. 1983.L'Iboga, psychotrope africain (Iboga, an African Psychotropic Agent). Psychotropes Vol. 1(1):11-27.

Goutarel, R. 1954. Recherches sur quelques alcaloïdes indoliques et leurs relations avec le métabolisme du tryptophane et de la dihydroxyphenylalanine (Research on some indole alkaloids and their relations with the metabolism of tryptophan and dihydroxyphenylalanine). Thesis, Doctor of Science Degree, Paris.

Goutarel, R., Janot, M.M., Mathys, F., and Prelog, V., 1953. Structure de l'ibogaïne (The structure of ibogaine), C.R. Acad. Sci. 237, 1718.

Goutarel, R., Janot, M.M., Prelog, V., and Taylor, W.I., 1950. Helv. chim. Acta 33, 150, 164.

Haller, A., and Heckel, E., 1901. Sur l'ibogaïne, principe actif d'une plante du genre Tabernaemontana, originaire du Congo (Concerning ibogaine, the active principle of a plant of the genus Tabernaemontana native to the Congo) C.R. Acad. Sci. 133:850-853.

Khuong-Huu, F., J.P. Leforestier, G. Maillard and R. Goutarel, 1978. C.R. Acad. Sci. 270, 2070, 2072.

Lambert, M., 1901. Sur l'action physiologique de l'iboga (On the Physiological Action of Iboga), C.R. Soc. Biol., 53:1096-1097.

Lambert, M., 1902. Sur les propriétés physiologiques de l'ibogaïne(On the Physiological Properties of Ibogaine), Arch. int. Pharmacodynamie et Thérapie, 10:101-120).

Lotsof, H.S. 1990. Personal communication.

Lotsof, H.S. 1990. Personal communication. [The Max Cantor interviews have since been published in the San Diego-based journal The Truth Seeker: 1990, Vol. 117(5):23-26].

Lotsof, H.S. 1989. U.S. Patent No. 4,857,523.

Lotsof, H.S. 1986. U.S. Patent No. 4,587,243.

Lotsof, H.S. 1985. U.S. Patent No. 4,499,096.

Lotsof, H.S. 1991. U.S. Patent No. 5,026,697.

Maisonneuve, I.M.; Keller, R.W. Jr.; and Glick, S.D. 1991. Interactions ibogaine, a potential anti-addictive agent, and morphine: an in vivo microdialysis study. European J. Pharmacol. 199: 35-42.

Moody, R.A.: Life After Life: The Investigation of a Phenomenon, Survival of Bodily Death, Walker & Co., 1988. The Light Beyond, Bantam, 1989.

Mueller, J.M.; Schlittler, E.; Bein, H.J. 1952. Experientia Vol. 8:338.

Naranjo, C. 1969. Psychotherapeutic possibilities of new fantasy-enhancing drugs. Clinical Toxicology Vol. 2(2):209.

Neu, Henri (Father). 1885. Archives générales des Pères du Saint-Esprit Vol. 148-B-i.

Phisalix, M.C. 1901. Action physiologique de l'ibogaïne (Physiological action of ibogaine). C.R. Acad. Sci. Vol. 53:1077.

Pouchet, G. and Chevalier, J. 1905.Note sur l'action pharmacologique de l'ibogaïne. Sur l'action pharmacodynamique de l'ibogaïne (Note on the pharmacological action of ibogaine. On the pharmacodynamic action of ibogaine), Bull. Gén. de Thérapeutique.

Prioux-Guyonneau, M.; Rapin, J.R.; Wepierre, J. 1977. J. Pharmacol. Paris Vol. 8(3):383.

Raymond-Hamet & Vincent, D. 1960. C.R. Soc. Biol. Vol. 154:2223; Raymond-Hamet; Vincent, D.; Parant, M. 1956. C.R. Soc. Biol. Vol. 150:1384; Vincent, D. & Séro, I. 1942. Travaux Membres Soc. Chim. Biol. Vol. 24:1352.

Raymond-Hamet 1946. C.R. Acad. Sci. Vol. 223:757; 1943. Bull. Soc. Chim. Biol. Vol. 25:200; 1942. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. Vol. 9:620; 1941. C.R. Acad. Sci. Vol. 212:768; 1940. C.R. Soc. Biol. Vol. 134:541; 1940. C.R. Soc. Biol. Vol. 133:426; 1939. Arch. Int. Pharmacology Vol. 63:27.

Raymond-Hamet 1941. L'iboga, drogue défatigante mal connue (Iboga, a poorly known antifatigue drug). Bull. Acad. Med. Vol. 124:243.

Sabom, M.B. Recollections of Death, Harper & Row, 1982.

Schlittler, E., Burckhard, C.A., Gellert, E. 1953. Die Kalischmelze des Alkaloides Ibogain, Helv. Chim. Acta 36:1337.

Schneider, J.A. and Rinehart, R.K. 1957. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Vol. 110(1):92.

Schneider, J.A. and Sigg, E.G. 1957. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. Vol. 66:765.

Schneider, J.A. 1956. Experientia Vol. 12:323.

Sershen, H., Hashim, A., Harsing, L., Lajtha, A. Ibogaine antagonizes cocaine-induced locomotor stimulation in mice. (In press. J. of Life Sciences.)

Séro, I. 1944. Une apocynacée d'Afrique équatoriale (An Apocynacea from Equatorial Africa). Thesis, Doctor of Pharmacy, Toulouse.

Vincent, D. and Séro, I, 1942. Action inhibitrice de Tabernanthe iboga sur la cholinestérase du sérum (The inhibitory action of Tabernanthe iboga on serum cholinesterase), C.R. Soc. Biol. 136:612-614.

Wurman, M. 1939. Contribution à l'étude expérimentale et thérapeutique d'un extrait de Tabernanthe manii d'origine gabonaise (Contribution to the experimental and therapeutic study of an extract of T. manii from Gabon). Thesis, Doctor of Medicine Degree, Paris.

Zetler, G. & Lessau, W. 1972. Pharmacology Vol. 8:235.

For further information about ibogaine, please refer to the Ibogaine Dossier at www.ibogaine.org (US) or www.ibogaine.desk.nl (Europe).